Shielding of Electrosmog: Some Observations (part 3)

Today I go all empirical and stuff my Motorola G23 in a biscuit tin

The question was asked…

If you have a Faraday box, does it actually cut em transmissions when mobile phones are put inside?

To which my reply was…

Providing the mesh is finer than the wavelength and there are absolutely no gaps, then yes, the cage will attenuate RF EMR. I shall demonstrate this in a future article.

We are now in the future and here is that promised article.

I love simple experiments. The fewer the components the better imho, so today I fancied running a very simple experiment using the perfect Faraday box… a biscuit tin! Not any old biscuit tin neither but a 2017 vintage tin that once contained 450g of Waitrose & Partners All Butter Shortbread; the bonus being it looks like a giant sixpence. Herewith said tin along with the rest of my apparatus:

Sitting on my log book is my trusty wooden ruler to ensure the leading edge (top) of the phone is placed 10cm from the leading edge (top) of the GQ Electronics EMF-390. You’ll also see a Staedtler Tradition 2B pencil. Pencils are import devices when it comes to experimentation and I wonder just how many have been utilised in the advances made in science since the eighteenth century.

I say the eighteenth century for the modern pencil as we know it – according to Brave Search AI - was invented in 1795 by Nicolas-Jacques Conté, a scientist serving in Napoleon Bonaparte's army. Conté developed a method of mixing powdered graphite with clay and forming the mixture into rods that were then fired in a kiln. This process allowed for the adjustment of pencil hardness by varying the ratio of graphite to clay. Prior to this, in the late 16th century, an Italian couple named Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti invented the first wooden pencil by hollowing out a flat rod of juniper wood and fitting the lead inside However, this innovation was not mass-produced until the 17th century. So there you go.

I ‘heart’ pencils and confess to recently purchasing a box of 12 Staedtler Tradition 2B along with a box of 12 Staedtler Tradition B. This extravagant behaviour is actually a form of self-defence, for Mrs Dee has the habit of borrowing my pencils (she being a musician and composer) and they never seem to make it back to my office. In fact, they never seem to show up anywhere ever again, and I suspect there may be a worm hole next to the metronome along with another Einstein-Rosen Bridge near the TV remote table.

Cage Madness

As for my choice of using a biscuit tin, there is method in this madness. Normally Faraday cages are just that: a wire cage with lots of holes whose spacing is slightly smaller than the wavelength of the EMR that needs to be screened out. A wire cage makes sense ‘coz sheet metal costs heaps of cash money in comparison and there may well be a need for ventilation (e.g. electronic components).

So how fine does the mesh need to be to interfere with a mobile phone signal?

Well, if we assume yer typical 2.4 GHz carrier wave for the 3G/4G cellular networks commonly in use today then a quick stab at my trusty hand-held calculator reveals a wavelength of 0.1249 metres, or 125 mm if you prefer weeny units. That’s quite a big mesh and you could almost play ping pong through it. The precise level of attenuation for a 2.4 GHz cellular signal as offered by a 125 mm Faraday mesh is a complex affair, and beyond my ability as a baker of biscuits to pen worthy comment. Scholarly articles are needed here and a starting point is this Wiki article.

I don’t have mesh to play with but I do have antique biscuit tins with tight-fitting lids, these having the advantage of shielding all EM frequencies (continuous Faraday shield and all that); and smelling nice into the bargain: hence their use! Some rather concerned folk may want to know the size of mesh needed to screen 60 GHz cellular signals and my trusty hand-held calculator reveals 5 mm.

One Little Fact

One little fact that I’d like to point out at this… er… point (that tends to get lost on folk) is that the sun also kicks out EMR, and 60 GHz can be found within its broad EM emission spectrum. A good place to start is the Wiki article on solar radio emissions, but my favourite summary can be found in a blog called The Radio Sun on the Prima Luce Lab website.

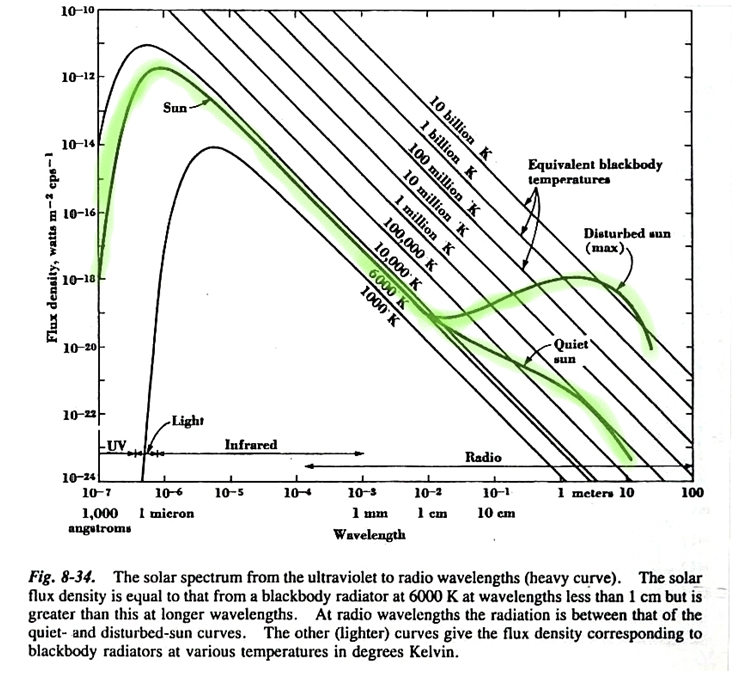

The second slide depicted in this blog is sourced from Radio Astronomy (2nd Edition) by J D Kraus (Cygnus-Quasar Books 1986), an online reader for which may be found here. Turn to page 218 and there it shall be; here it is again after a bit of tarting-up:

I’ve run a pale green highlighter over the measured curve for the sun and we can see that EM wavelengths of between 1 mm and 1 cm are mostly certainly evident at 6000K, with flux densities around 10-18 Watts m-2 cps-1. What this means in plain English is that the Earth and its inhabitants have been bathing in 60 GHz EMR and beyond (i.e. infrared, UV and visible light) since the solar system came into being and the sun took its first puff. Not a lot of people seem to appreciate this factoid, but there it is for all to see!

Another little-discussed factoid concerns absorption of EMR by the tissues of the body. They say that beauty is skin deep and so is absorption of EMR in the Gigahertz range. Ironically, when it comes to absorption of radiation by the body we should have been concerned with 2G way back, and especially anything transmitting below 100 MHz way, way back! A paper I quite like is Estimation of E-Field inside Muscle Tissue at MICS and ISM Frequencies Using Analytic and Numerical Methods by Mohammed & Saber (2014); this is worth a few biscuits and a fresh pot.

Right, so, rant over and tin foil trousers back on: I think it is high-time I released the results of my micro study…

Results

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to John Dee's Private Passion to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.